|

|

Dessalines

Is Rising!!

Ayisyen: You Are Not Alone!

***************

McClelland: You have no right to speak of my story, I

did not give you authorization

***************

Author hopes 'genius grant' will shine on Haiti

*********************

Black

is the Color of Liberty

*********************

A

Haitian Family Linked by Love Must Learn to Live on Separate shores

Audio excerpt

***************

In

Loving Memory

***************

Book

Reviews - Dantò Archives

***************

A

Haitian Tragedy: Brothers Yearn in Vain

|

| |

|

| To subscribe,

write to erzilidanto@yahoo.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Carnegie

Hall Carnegie

Hall

Video Clip |

| |

No

other national

group in the world

sends more money

than Haitians living

in the Diaspora |

|

|

The

Red Sea |

|

|

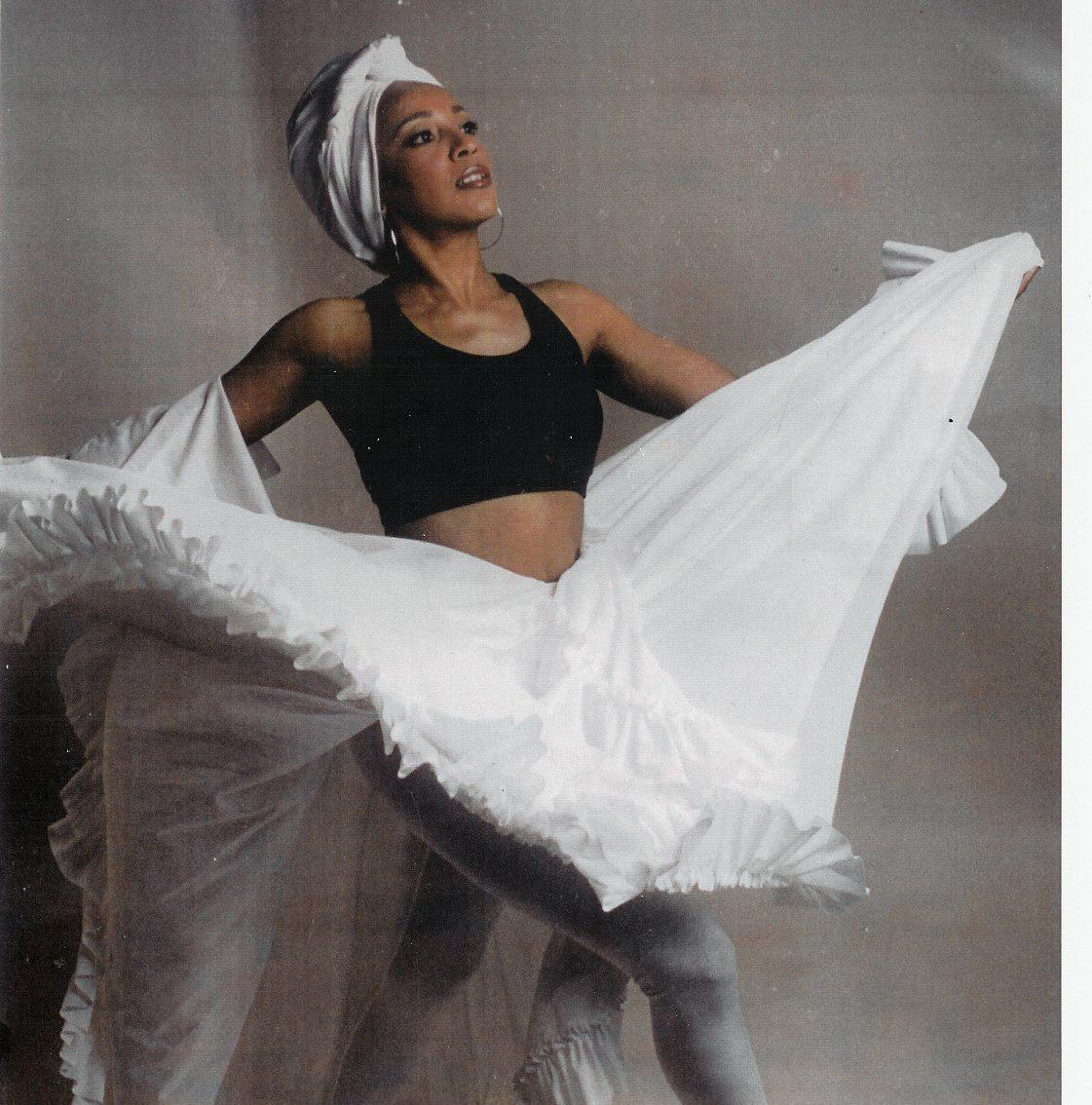

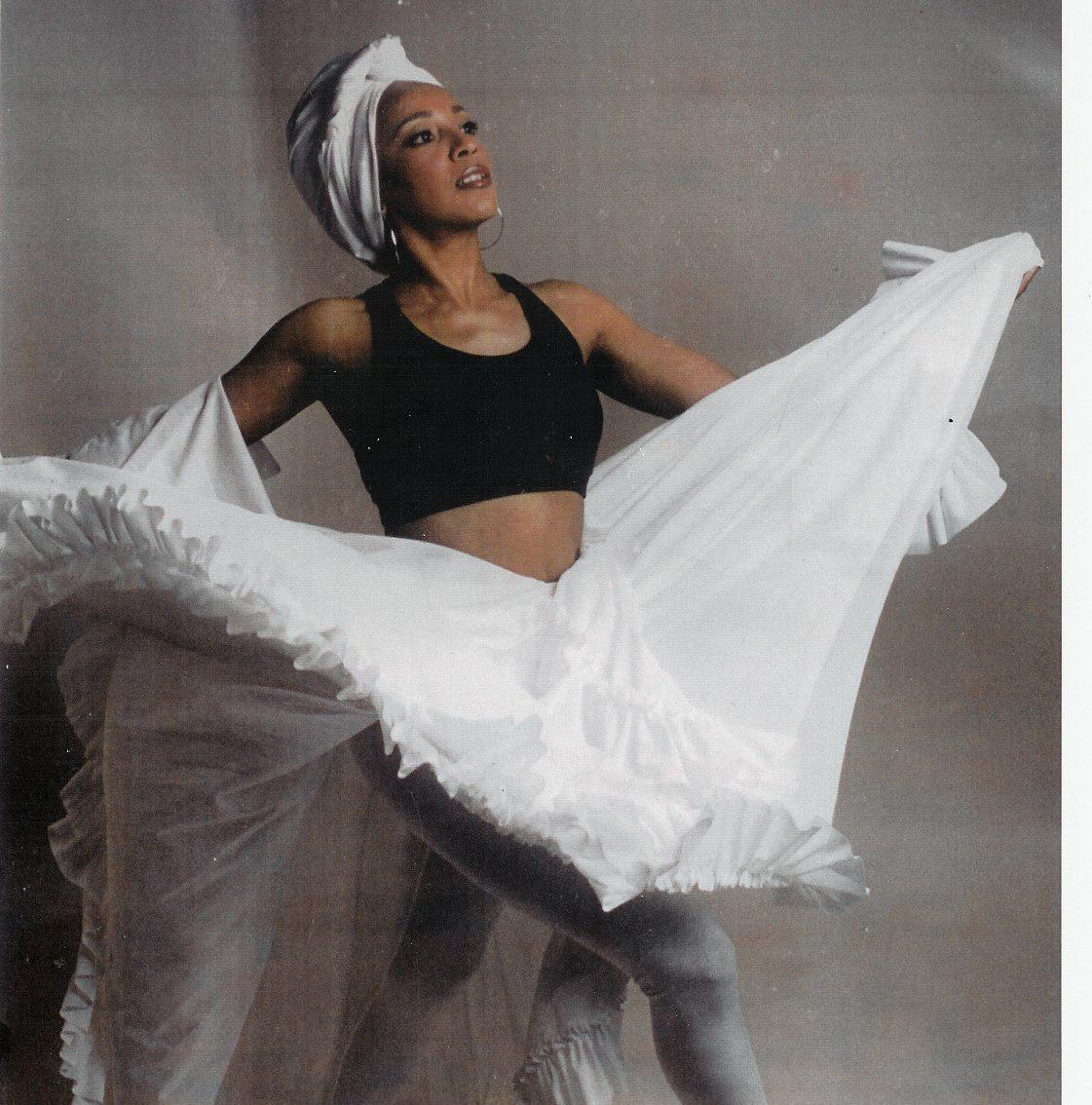

Ezili Dantò's master Haitian dance class (Video clip)

Ezili's

Dantò's Ezili's

Dantò's

Haitian & West African Dance Troop

Clip

one -

Clip two

|

|

So

Much Like Here- Jazzoetry CD audio clip

|

|

|

Ezili Danto's

Witnessing

to Self

Update

on

Site Soley |

|

|

| RBM

Video Reel

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Haitian

immigrants

Angry with

Boat sinking

|

|

| A

group of Haitian migrants arrive in a bus after being

repatriated from the nearby Turks and Caicos Islands,

in Cap-Haitien, northern Haiti, Thursday, May 10, 2007.

They were part of the survivors of a sailing vessel crowded

with Haitian migrants that overturned Friday, May 4 in

moonlit waters a half-mile from shore in shark-infested

waters. Haitian migrants claim a Turks and Caicos naval

vessel rammed their crowded sailboat twice before it capsized.

(AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Dessalines'

Law

and Ideals

|

|

Breaking

Sea Chains |

|

Little

Girl Little

Girl

in the Yellow

Sunday Dress

|

|

| Anba

Dlo, Nan Ginen |

|

| |

|

|

Ezili

Danto's Art-With-The-Ancestors

Workshops - See, Red,

Black & Moonlight series or Haitian-West African

Clip

one -Clip

twoance performance |

|

|

In

a series

of articles written for the October 17, 2006 bicentennial

commemoration of the life and works of Dessalines, I wrote

for HLLN that: "Haiti's liberator and founding father,

General Jean

Jacques Dessalines, said, "I Want

the Assets of the Country to be Equitably Divided"

and for that he was assassinated by the Mullato sons of France.

That

was the first coup d'etat, the Haitian holocaust - organized

exclusion

of the masses, misery, poverty and the impunity of the economic

elite

- continues (with Feb. 29, 2004 marking the 33rd coup d'etat).

Haiti's peoples continue to

resist the return of despots,

tyrants and enslavers who wage war on the poor

majority and Black, contain-them-in poverty through neocolonialism'

debts, "free trade" and foreign "investments."

These neocolonial tyrants refuse to allow an equitable division

of wealth, excluding the majority in Haiti from sharing in

the

country's wealth and assets." (See also, Kanga

Mundele: Our mission to live free or die trying, Another Haitian

Independence Day under occupation; The

Legacy of Impunity of One Sector-Who killed Dessalines?;

The Legacy of Impunity:The

Neoconlonialist inciting political instability is the problem.

Haiti is underdeveloped in crime, corruption, violence, compared

to other nations,

all, by Marguerite 'Ezili Dantò' Laurent |

| |

|

|

|

|

| No

other national group in the world sends more money than Haitians

living in the Diaspora |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

***************

...."[I]t is not our way to let our grief silence

us." (Edwidge Danticat in "Brother, I'm Dying"... (Brother,

I'm Dying )

********

***************

Media

Lies and Real Haiti News

***************

The Slavery in the Haiti the Media Won’t Expose

********

"a time comes when silence is betrayal… Every man of

humane convictions must decide on the protest that best suits his convictions,

but we must all protest" -- Martin Luther King

****************

|

|

|

|

|

Haitian-American

author, Edwidge Danticat, signs a copy of her book "Krik? Krak!"

for Pinecrest student Gabriel Seidner,17, Wednesday morning following

a question and answer session at the school. Haitian-American

author, Edwidge Danticat, signs a copy of her book "Krik? Krak!"

for Pinecrest student Gabriel Seidner,17, Wednesday morning following

a question and answer session at the school.

Photo:Emily Michot/Miami Herlad Staff |

Miami author Edwidge

Danticat wins `Genius Award'

*

Haiti-born writer Edwidge Danticat has won the prestigious MacArthur

Foundation fellowship, which comes with $500,000.

by Jacqueline Charles, jcharles@MiamiHerald.com,

Miami Herald,

Sept. 22, 2009

*

Miami writer Edwidge Danticat was holding her 9-month-old daughter,

Leila, while trying to read the computer screen when the phone rang.

``Are you sitting down?'' the caller asked.

``Yes. I am holding my baby,'' she said.

``Put the baby down.''

An award-winning author who was born in Haiti, Danticat, 40, learned

she had just won the biggest honor of her career: the John D. and Catherine

T. MacArthur Foundation `Genius Award,' which carries a $500,000 ``no

strings attached'' prize.

``I am extremely grateful,'' said an ecstatic Danticat, one of 24 winners

named this year as a fellowship winner. ``I am still wrapping my brain

around it, trying to see how I can do it justice.''

Daniel Socolow, who directs the fellows program and called Danticat

with the news, said the writer emerged from a pool of hundreds of creative

leaders, nominated by individuals for their creative genius and potential.

The final selection, he said, was made by an anonymous 12-member committee

and after writing ``thousands and thousands of other people about them.''

In addition to Danticat, this year's winners include Jill Seaman of

Sudan, an infectious-disease specialist, Lynsey Addario of Turkey, a

photojournalist, and Peter Huybers of Massachusetts, a climate scientist

at Harvard.

``We look at the work they've done, but at the end of the day it's a

calculation this is somebody worthy of our investment,'' Socolow said.

``We don't know what they will do next; we just know they are likely

to do something spectacular. It is betting on their future.''

Socolow said Danticat, a compelling novelist known for capturing human

endurance and perseverance through her books, ``has wonderful promise

yet ahead to do even more powerfully what she does.''

Danticat made her debut as a novelist in 1994 with Breath, Eyes, Memory.

In all, she has written eight books, recently finished a collection

of essays and is working on a new novel.

HAITIAN LIFE

Through her works, she has amassed a wide range of fans with her simple

prose and themes of isolation, human struggle, cultural survival --

all set against the complex backdrop of Haiti's complex history and

immigrant life.

Her most recent book was the semi-autobiographical Brother, I'm Dying.

The memoir is a tribute to her 81-year-old uncle, Joseph Dantica, a

minister who fled to Miami seeking refuge from Haiti's political and

gang-ridden turmoil only to die in the custody of U.S. immigration authorities.

His plight and life are chronicled through Danticat's memories as a

child growing up in Haiti under his care. The book won the National

Book Critics Circle Award, among others.

Past notable winners including Dr. Paul Farmer, a Harvard anthropologist

and infectious-disease specialist who won the award in 1993 for his

work combating HIV/AIDS in Haiti.

`IT LIBERATES YOU'

As a writer, Danticat says she always yearns for the time and peace

of mind as she brings her characters -- ordinary people facing hardship

and struggle -- to life. This award gives her that, she said.

``What this does is it liberates you to really concentrate on your work,''

she said. ``I have always tried to pace myself not to live extravagantly,

so I can earn the time I need to write.''

After receiving the news, Danticat said she gasped, then called her

husband Faidherbe ``Fedo'' Boyer and told him the news. He and daughter

Mira were the only ones who knew for a week.

Her mother, who lives in New York, only learned the news Monday.

Meanwhile, she says she has no idea who nominated her, but is extremely

grateful.

``You just get this call one day,'' she said. ``It is so gratifying

to know people out there think I deserve more time to work.''

***************

Author

hopes 'genius grant' will shine on Haiti

By JONATHAN M. KATZ (AP)

– Sept. 23, 2009

|

|

|

AP - In this March

6, 2008 file photo, novelist Edwidge Danticat speaks during the

National Book Critics Circle awards ceremony in New York. Danticat

was named recipient of a MacArtur foundation "genius grant,"

Monday Sept. 21, 2009. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File) |

PORT-AU-PRINCE,

Haiti — Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat hopes her "genius

grant" from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation will

bring attention to the wealth of talent struggling to be heard in her

impoverished Caribbean homeland.

The 40-year-old novelist and short story writer, who has won previous

prizes for her depiction of the travails of Haitian migrants, was one

of 24 artists, scientists, journalists and others named Tuesday as fellows

by the Chicago-based organization. Each receives a $500,000 grant over

the next five years.

"My experience or whatever talent I have is not unique: there are

probably thousands of others like me in Haiti or here," Danticat

in a phone interview from Miami. "The only difference is I've had

some opportunity."

The foundation's online biography cites her "graceful, deceptively

simple prose" and "moving and insightful depictions of Haiti's

complex history" that "reminds us of the power of human resistance,

renewal, and endurance against great obstacles."

Danticat's 2007 memoir, "Brother, I'm Dying," told the stories

of her father and uncle's struggles in Haiti and the United States.

Her early novel "Breath, Eyes, Memory" was an Oprah's Book

Club pick. Other titles include the noted short story collection "Krick?

Krack!" and "The Farming of Bones," a retelling of the

1937 massacre of 20,000 to 30,000 Haitian workers in the neighboring

Dominican Republic.

Danticat had no idea she was even being considered for the "genius

grant" until program director Daniel Socolow called her Miami home

early last week. She was holding her 9-month-old daughter, Leila.

"He suggested I put the baby down and then he told me (I had won),"

Danticat recalled. She laughed, "I was glad I was sitting down."

After giving out the awards, the foundation sits back and allows the

recipients, who must be U.S. citizens or residents, to do whatever they

want with it.

"Her work is quite extraordinary," Socolow told the AP by

phone from Chicago. "We just bask in the pleasure of what she might

do."

Danticat, who most recently visited Haiti in March to see family, says

the prize will enable her to take time off from teaching and focus on

writing, including a novel still in the works.

The author, who was the editor of a 2001 collection of writing by Haitian-Americans,

said she also intends to quietly help other writers develop their talents.

Raised in Port-au-Prince's Bel Air slum, now a crumbling garbage-strewn

district that has been a hotbed of gang and government violence through

the years, she was taken by her parents to the United States at age

12. She attended Barnard College in New York and then earned a master's

degree at Brown University.

"I'm thinking about the journey that brought us here. There are

so many people who are probably more talented and more gifted than me

but have not had the opportunities," she said.

Previous authors to win the MacArthur grant include Thomas Pynchon,

David Foster Wallace and Andrea Barrett. Paul Farmer, the recently named

U.N. deputy special envoy for Haiti, was picked in 1993 in large part

for his work as a physician in Haiti.

In an overcrowded, impoverished country where most families scrape by

on less than $1 a day, many with the help of money sent back from relatives

abroad, Danticat's grant money will likely attract notice.

Still, Haitian artists said the critical attention to one of their own

counts for more in the long run.

"Edwidge's writing shines a light on Haiti," said Evelyne

Trouillot, an author and friend who lives in Port-au-Prince. "Not

only the poverty ... but the struggle to show that Haitians are human."

***************

Tragedy transcended, The

Boston Globe

Danticat's memoir emphasizes the enduring love

between two brothers, now united in death

|

|

|

| Edwidge

with daughter Mira, whom she named after her father. "Hopefully

I'll have an uninterrupted lifetime with her," she writes,

"a lifetime to plant some things that have been uprooted

in me and uproot others that have been planted." (NEW YORK

TIMES/CINDY KARP) |

By Renée Graham | September 16, 2007

Brother, I'm Dying

By Edwidge Danticat

Knopf, 272 pp., $23.95

They are together now, two loving brothers separated for 30 years by

geography and political circumstances, at last reunited.

Yet there is no glory, no sense of resolution or injustice made right.

These were lives deprived of happy endings or tearful reunions. They

are together only in death, sharing a grave site and a tombstone in

the compacted soil of a cemetery in Queens, N.Y.

"I wish I were absolutely certain that my father and uncle are

now together in some tranquil and restful place, sharing endless walks

and talks beyond what their too-few and too-short visits allowed,"

Edwidge Danticat writes of her father and uncle in her devastating memoir,

"Brother, I'm Dying."

"I wish I knew that they were offering enough comfort to one another

to allow them both not to remember their distressing, even excruciating,

last hours and days." Danticat knows there are no such guarantees,

only the reality of two earnest lives pockmarked by tragedy.

As with her earlier, award-winning works, including her marvelous story

collection "Krik? Krak!" and best-selling novel "The

Dew Breaker," Danticat finds poetic truth in the relentless hardships

of her native Haiti and its people. This time, it's the elegiac story

of her father, Mira, who left Haiti for New York when Danticat was 2

years old. When her mother followed two years later, Mira's older brother,

Joseph, raised the author and her brother Bob for eight years. It is

the story of two men in two countries trying to do the best they can

for their families, two men whose connection remains resolute through

decades, even though they were rarely together.

And this is also Danticat's story. As the book begins, she finds out

she is pregnant with her first child, but it is bittersweet news because,

on the same day, her father is diagnosed with late-stage pulmonary fibrosis.

Imagining life without her father takes Danticat back to the years when

his absence was temporary, but no less wrenching, times when her father

existed only in the half-page, three-paragraph letters he would send

to her uncle every other month.

Danticat's memories span more than 50 years of her family's history,

bookended by recent events tinged by birth and death, sadness and hope.

Coupled with official documents, these are the "borrowed recollections

of family members" and stories shared over the years with Danticat

by Mira and Joseph, her two fathers.

Given the endless turmoil in Haiti - and the bloodthirsty reign of "Papa

Doc" Duvalier and his ferocious thugs, the Tonton Macoutes - Mira,

a tailor, left his homeland for New York. He had a one-month tourist

visa, but had no intention of returning. Joseph, meanwhile, was a preacher

who long resisted the lure of America, and the ever-present threats

of local thugs, to remain in his troubled island home. So dedicated

was he to his congregation, he remained their pastor even after his

voice was silenced by a radical laryngectomy.

When Joseph finally decides to join his brother in the States, the results

are unexpectedly tragic; he dies in a Miami detention center while waiting

to see if he'll be granted asylum. Still, for all the palpable sorrows

throughout this memoir, it is also a story about a family's love, and

the profound bond among brothers, parents, and children.

Danticat is such an elegant writer, her prose so free of showy flourishes,

that her words can seem deceptively simple. She has the confidence to

allow the story to tell itself, and find its own pace. Emotional, but

never mawkish, "Brother, I'm Dying" is a stellar achievement

from a writer whose stunning talents continue to soar and amaze.

Renée Graham is a freelance writer.

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.

|

|

|

Impounded Fathers

by Edwidge Danticat, Op-Ed Contributor,

New York Times,

June 17, 2007 | MIAMI

MY father died in May 2005, after an agonizing battle with lung disease.

This is the third Father’s Day that I will spend without him since

we started celebrating together in 1981. That was when I moved to the

United States from Haiti, after his own migration here had kept us apart

for eight long years.

My father’s absence, then and now, makes all the more poignant

for me the predicament of the following fathers who also deserve to

be remembered today.

There is the father from Honduras who was imprisoned, then deported,

after a routine traffic stop in Miami. He was forced to leave behind

his wife, who was also detained by immigration officials, and his 5-

and 7-year-old sons, who were placed in foster care. Not understanding

what had happened, the boys, when they were taken to visit their mother

in jail, asked why their father had abandoned them. Realizing that the

only way to reunite his family was to allow his children to be expatriated

to Honduras, the father resigned himself to this, only to get caught

up in a custody fight with American immigration officials who have threatened

to keep the boys permanently in foster care on the premise that their

parents abandoned them.

There is also the father from Panama, a cleaning contractor in his 50s,

who had lived and worked in the United States for more than 19 years.

One morning, he woke to the sound of loud banging on his door. He went

to answer it and was greeted by armed immigration agents. His 10-year

asylum case had been denied without notice. He was handcuffed and brought

to jail.

There is the father from Argentina who moves his wife and children from

house to house hoping to remain one step ahead of the immigration raids.

And the Guatemalan, Mexican and Chinese fathers who have quietly sought

sanctuary from deportation at churches across the United States.

There’s the Haitian father who left for work one morning, was

picked up outside his apartment and was deported before he got a chance

to say goodbye to his infant daughter and his wife. There’s the

other Haitian father, a naturalized American citizen, whose wife was

deported three weeks before her residency hearing, forcing him to place

his 4-year-old son in the care of neighbors while he works every waking

hour to support two households.

These families are all casualties of a Department of Homeland Security

immigration crackdown cheekily titled Operation Return to Sender. The

goals of the operation, begun last spring, were to increase the enforcement

of immigration laws in the workplace and to catch and deport criminals.

Many women and men who have no criminal records have found themselves

in its cross hairs. More than 18,000 people have been deported since

the operation began last year.

So while politicians debate the finer points of immigration reform,

the Department of Homeland Security is already carrying out its own.

Unfortunately, these actions can not only plunge families into financial

decline, but sever them forever. One such case involves a father who

was killed soon after he was deported to El Salvador last year.

“Something else could be done,” his 13-year-old son Junior

pleaded to the New York-based advocacy group Families for Freedom, “because

kids need their fathers.”

Right now the physical, emotional, financial and legal status of American-born

minors like Junior can neither delay nor prevent their parents’

detention or deportation. Last year, Representative José E. Serrano,

a Democrat from New York, introduced a bill that would allow immigration

judges to take into consideration the fates of American-born children

while reviewing their parents’ cases. The bill has gone nowhere,

while more and more American-citizen children continue to either lose

their parents or their country.

Where are our much-touted family values when it comes to these children?

Today, as on any other day, they deserve to feel that they have not

been abandoned — by either their parents or their country.

Edwidge Danticat is the author of the forthcoming “Brother,

I’m Dying,” a memoir.

*************** |

********

Haitian Fathers

by Jess Row

September 9, 2007 | www.nytimes.com

Joseph Dantica, one of two brothers at the heart of this family memoir,

was a remarkable man: a Baptist minister who founded his own church and

school in Port-au-Prince, Haiti; a survivor of throat cancer who returned

to the pulpit using a mechanical voice box; a loyal husband and family

man who raised his niece Edwidge Danticat to the age of 12, when she joined

her parents in Brooklyn. (The "t" at the end of "Danticat"

is the result of a clerical error on her father's birth certificate. )

When Dantica fled Haiti in 2004, after a battle between United Nations

peacekeepers and chimeres "gang members" destroyed his church

and put his life in jeopardy, he was 81, with high blood pressure and

heart problems, and yet for 30 years had resisted his family's pleas to

emigrate to the States. He intended to return and rebuild his church as

soon as the fighting stopped. But to the Department of Homeland Security

officers who examined him in Miami, his plea for temporary asylum meant

he was simply another unlucky Haitian determined to slip through their

fingers. When he collapsed during his "credible fear" interview

and began vomiting, the medic on duty announced, "He's faking."

That refusal of treatment cost him his life: he died in a Florida hospital,

probably in shackles, the following day.

BROTHER, I'M DYING By Edwidge Danticat.

272 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $23.95.

How does a novelist, who trades in events filtered through imagination

and memory, recreate an event so recent, so intimate and so outrageous,

an attack on her own loyalties and sense of deepest belonging? The story

of Joseph Dantica could be, perhaps will be, told in many forms: as a

popular ballad (performed, in my imagination, by Wyclef Jean); as Greek

tragedy; as agitprop theater; as a bureaucratic nightmare worthy of Kafka.

But Edwidge Danticat, true to her calling, has resisted any of these predictable

responses. "Anger is a wasted emotion," says the narrator of

"The Dew Breaker," her most recent novel; in telling her family's

story, she follows this dictum almost to a fault, giving us a memoir whose

cleareyed prose and unflinching adherence to the facts conceal an astringent

undercurrent of melancholy, a mixture of homesickness and homelessness.

Haunting the book throughout is a fear of missed chances, long-overdue

payoffs and family secrets withering on the vine: a familiar anxiety when

one generation passes to another too quickly. In the first chapter Danticat

learns she is pregnant with her first child just as her father, Mira,

receives a diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis and loses his livelihood as

a New York cabdriver after more than 25 years. At a family meeting, one

of his sons asks him, "Have you enjoyed your life?" Mira pauses

before answering, and when he does, he frames the response entirely in

terms of his children: "You, my children, have not shamed me. ...

You all could have turned bad, but you didn't. ... Yes, you can say I

have enjoyed my life."

That pause, and that answer, neatly encapsulates an unpleasant, though

obvious, truth: immigration often involves a kind of generational sacrifice,

in which the migrants themselves give up their personal ambitions, their

families, native countries and the comforts of the mother tongue, to spend

their lives doing menial work in the land where their children and grandchildren

thrive.

On the other hand, there is the futility, and danger, of staying put in

a country that over the course of Danticat's lifetime has spiraled from

almost routine hardship - the dictatorship of the Duvaliers and the Tontons

Macoute - to the stuff of nightmares. Danticat's father and uncle stand

on opposite sides of this bitter divide.

It is Joseph's story that takes up the better part of the book. He began

life in a farming family in the rural town of Beausejour, moved to Port-au-Prince

in the late 1940s to seek a better life and fell under the sway of the

populist leader Daniel Fignole, who became president but was deposed three

weeks later and was eventually replaced by Francois Duvalier. Joseph's

disenchantment with politics and gift for rousing oration led him to the

Baptist church, and for more than four decades he served as a pastor,

school principal and community leader, doing the quiet work of maintaining

and uplifting the people around him - including his large extended family.

Though he was a strong supporter of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, he served

as a witness and chronicler of the crimes and abuses committed by all

sides. Had his life and Haiti's history turned out differently, his records

and eyewitness reports - destroyed in the burning of his church - might

have been used as evidence in human rights tribunals bringing the country's

leaders to justice.

All of which makes what happened to him in 2004 the more outrageous. In

Danticat's recounting, the United Nations peacekeepers who arrived to

stabilize the country after Aristide was forced into exile appear far

more interested in battling local gangs than in serving the traumatized

civilian population. The Creole expression for this kind of governance

is mode soufle: "where those who are most able to obliterate you

are also the only ones offering some illusion of shelter and protection."

Joseph Dantica's greatest failing, it appears, was his refusal to cut

deals or strategize; his withdrawal from politics early in life left him

without the instincts or vocabulary to defend his church and himself.

He arrived in the United States holding a valid tourist visa, but because

of the circumstances and his intent to return later than he had originally

planned, he insisted on asking for "temporary asylum," not fully

comprehending what this meant. Had he not clung so stubbornly to his own

truth, he might still be alive.

After his brother was buried - against his wishes, not in Haiti but in

Queens - Danticat's father declared: "He shouldn't be here. If our

country were ever given a chance and allowed to be a country like any

other, none of us would live or die here." Danticat lets this stand

without comment; we are left to imagine how painful it must have been

for her and her American-born siblings to hear this sentiment spoken aloud.

Are Haitians in America immigrants, and the children of immigrants, or

exiles? Do they accept a hybrid identity, a hyphen, or do they keep alive

the hope of "next year in Port-au-Prince, " so to speak?

Of course, in one sense, it's a pointless question: when her parents couldn't

understand her "halting and hesitant Creole," Danticat reports,

they would respond, "Sa blan an di?" - "What did the foreigner

say?" She and her brothers, from all appearances, are fully, firmly

assimilated; her own success, as a writer of novels in a distinctly American

idiom - English being her third language - is the ultimate proof of that.

There is, however, such a thing as self-imposed, psychic exile: a feeling

of estrangement and alienation within one's adopted culture, a nagging

sense of homelessness and dispossession. "A man who repudiates his

language for another changes his identity," wrote E. M. Cioran, a

Romanian exile in Paris for nearly 60 years: "He breaks with his

memories and, to a certain point, with himself."

"Brother, I'm Dying," in its cool, understated way, begins to

gesture in that direction. Danticat's father died shortly after Joseph

and was buried under the same tombstone; she imagines them together again

in BeausEjour, reconciled and happy once more. But she makes no indication

of how she might reconcile these shattering events with her own near-miraculous

American odyssey. It's hard to imagine how anyone could.

*

Jess Row is the author of "The Train to Lo Wu," a collection

of stories. |

| ***************

|

| Fitting

together the pieces of a tragedy,

By Anna Mundow,

Boston

Globe

|

|

|

Edwidge

Dandicat - Nancy Crampton Edwidge

Dandicat - Nancy Crampton |

Edwidge Danticat was raised by her aunt and uncle in Haiti and joined

her parents in the United States when she was 12. Her peerless fiction

includes "Breath, Eyes, Memory" and "The Dew Breaker."

In 2004, when Danticat was pregnant with her first child and while her

father was dying of pulmonary fibrosis, her uncle, an elderly churchman,

was forced to flee the violence in Haiti.

Despite having documentation and having visited America before, a frail

Joseph Danticat was first detained by US Customs, then shackled and

imprisoned. Without his medication, he died within days. Earlier this

year, The New York Times reported that 62 immigrants have died in US

administrative custody since 2004. "Brother, I'm Dying" (Knopf,

$23.95), a model of grace and restraint, tells the story of Uncle Joseph,

of the Danticat family, and of their country.

Danticat spoke from her home in Miami.

Q: Was it hard for you to reveal yourself and your

family this way?

A: What made it less difficult was the fact that we

all had this grief in common. I'm very conscious of the self-indulgence

of writing about oneself, but there was more than just our pain happening,

for my uncle certainly but also for my father. It was a way of paying

tribute to them.

Q: This is part memoir, part reconstruction. What sources

did you draw on?

A: I drew a lot on the official documents of my uncle's

detention. The final document we got from the inspector general in Washington

was in fact a retelling of all the interviews in the process. It was

almost like one of those novels where you get the point of view of every

character, including my uncle's.

. . . We had to fight hard to get these papers under the Freedom of

Information Act. I also drew on stories from my aunt Zi, who was the

last person my uncle spent a lot of time with. It's a strange thing

to say, but I felt as if every other thing I had written was like training

for this.

Q: Did you feel that you were giving lives to people

we see - if at all - solely as victims?

A: I think that was the driving force. Going through

the detention bureaucracy with my uncle and going to see many doctors

with my father, you know that what they see is this old man who is poor,

who is Haitian. That he is a person is not of any concern to them. You

want to say, "This is a man, a great father, his life matters."

In fiction you do that when you write characters. But there's ambivalence

too, because there were parts I just wanted to keep for myself.

Q: When your uncle died in detention, was that your

first glimpse of a different America?

A: It really wasn't. My parents with their church used

to visit detainees at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. And here in Miami I used

to visit detention centers, so this was a reality I knew. I think that

made it more horrific, I couldn't lie to myself. Of course it's different

when it's someone you love. What was most striking to me was these people

who are supposed to speak for the government saying "It was his

time, we all have to die," calling my uncle's medicine "voodoo

medicine." Then we read the New York Times article about people

dying in detention, and it was the same story. Except that I was in

the fortunate position of having, if not a big mouth, then a big pen.

Other families haven't got that.

Q: Yes, one of the questions on the form the detaining

officer fills in is "Congressional or media interest?"

A: I know, I kept thinking if they had known I was

a writer would that have made a difference. It shows how important it

is to speak out, to share your story. I also kept feeling that if only

one person in the process had acted humanely and said this is a very

sick old man, things would have turned out differently.

Q: You ask "Was he going to jail because he was

black?" Was he?

A: Certainly because he was Haitian, because there

is a specifically unfavorable policy toward Haitian refugees, especially

in Miami. If it had been an 81-year-old Cuban or European asking for

asylum, I'm pretty sure he would have been treated differently.

Q: Why do you describe the most harrowing moments so

dispassionately?

A: I did not want to write an angry polemic. These

things speak for themselves. The details from the report, the medical

records of my uncle's death, I want the reader to come across those

and wonder how could someone have this information and make such disastrous

decisions for the life of an old man.

Q: Has your family had any redress?

A: None. The report from the inspector general of the

Department of Homeland Security concluded that nobody did anything wrong.

I guess this book is our only redress.

Anna Mundow is a correspondent for the Irish Times. She can be reached

via e-mail at ama1668@hotmail.com.

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.

********

BOOK

REVIEW

'Brother,

I'm Dying' by Edwidge Danticat

The

writer's childhood memories form a loving tribute to her father and

uncle.

by Donna

Rifkind,

September

9, 2007, LA

Times

Brother, I'm Dying

Edwidge Danticat

Alfred A. Knopf: 272 pp., $23.95

THERE is no guarantee that a distinguished fiction writer will produce

a successful memoir. Yet Edwidge Danticat -- the author of three elegant

and complex novels, including "Breath, Eyes, Memory," and

the story collection "Krik? Krak!" brings the same lucid storytelling

to "Brother, I'm Dying."

On the same day in 2004 that Danticat joyfully discovered she was pregnant

with her first child, her father, a 69-year-old Brooklyn taxi driver,

was diagnosed with end-stage pulmonary fibrosis.

Months later, her uncle Joseph, a Baptist pastor who had raised Danticat

in Haiti during much of her childhood, was forced to flee the riot-torn

Port-au-Prince neighborhood in which he had lived for more than 50 years.

Age 81 and ailing, Joseph flew to America to stay with his brother's

family but was unjustly detained by the Department of Homeland Security

in Miami, where, under harsh conditions, he died in custody.

Revisiting this "wondrous and terrible" intersection of events,

and roaming backward through the history of her family and her native

country, Danticat struggles to fashion a cohesive narrative. Like a

burial, her account is a final, loving act on behalf of her father and

uncle. "I am writing this," she flatly states, "only

because they can't."

If rigor is elusive in such an intricate account -- one that expands

outward to include the history of U.S. involvement in Haiti since 1915;

violence and fear during the Duvalier reign and beyond; and post-Sept.

11 immigration policy -- emotional clarity is abundant.

It thrives, as it does in all of Danticat's work, in small, piercing

scenes. In 1973, her mother leaves Haiti to join her father in America,

leaving 4-year-old Edwidge and her younger brother to be raised by Joseph

and his wife. The airport goodbye is excruciating: "I wrapped my

arms around her stockinged legs to keep her feet from moving. She leaned

down and unballed my fists as Uncle Joseph tugged at the back of my

dress, grabbing both my hands, peeling me off her."

On the streets of Port-au-Prince, when she's 9, Danticat serves as her

uncle's interpreter after throat cancer and a laryngectomy render him

mute. She agonizes for him as neighbors gawk at his tracheotomy hole.

"[A]ll I could think to do was imagine a wall around him, a roaming

fortress that would follow him everywhere he went and shield him from

derision."

At age 12, Danticat and her brother reunite with their parents and two

U.S.-born younger siblings in Brooklyn. As she matures in America, she

retains her role as the family voice, telling its stories, interpreting

its dreams and nightmares as she had once spoken for her wordless uncle.

In the Miami mortuary where Joseph lies in November 2004, "exiled

finally in death," the funeral manager tries to persuade the pregnant

Danticat not to view the body. She disregards him, recognizing that

"the dead and the new life were already linked, through my blood,

through me." They're linked through her eloquence as well, for

as she says, citing a Haitian folk tale, "[I]t is not our way to

let our grief silence us."

*********************************************

|

|

Author

Edwidge Danticat reads an excerpt from her new memoir 'Brother, I'm

Dying' (3:25) Author

Edwidge Danticat reads an excerpt from her new memoir 'Brother, I'm

Dying' (3:25)

********

BOOK

REVIEW

A

Haitian Family, Linked by Love Must Learn to Live on Separate Shores

Edwidge

Danticat has written a moving tribute to her father and uncle, the two

men who raised her.

by Yvonne

Zipp ,

September

11, 2007, The

Christian Science Monitor

Novelist Edwidge Danticat grew up with two papas – her dad, Mira,

who left Haiti for America when she was 2, and her Uncle Joseph, a pastor

who raised Danticat and her younger brother, Bob, until they were able

to join their parents in New York when she was 12.

Almost two decades later, in 2004, Joseph was forced to flee Haiti after

gangs threatened to kill him. Despite the fact that he had a valid visa

and a passport, the United States government imprisoned the octogenarian,

who was dead within days. Earlier that year – on the same day

that she discovered that she was pregnant – Danticat found out

that Mira had been diagnosed with a fatal illness.

Now, Danticat has written a beautiful memoir to both her fathers. If

there's such a thing as a warmhearted tragedy, Brother, I'm Dying is

a stunning example. As she did in her powerful novels, such as 2004's

"The Dew Breaker," Danticat uses the personal to show the

impact of a whole country's legacy. But she does so in a way that avoids

rage or bitterness – an amazing feat since it's not possible to

even read about her uncle's treatment in US custody without a deep-burning

anger. But the main characteristics of the memoir are the generosity,

strength, and dignity of the two men, and the love Danticat has for

both.

"Brother, I'm Dying" also encompasses the emotional lives

of both halves of a diaspora: those who leave and those who remain behind.

As a child, she cherished the rare links to her parents, who were only

able to make one trip to Haiti during the eight years between the time

her mother left to join her father and her own trip.

Before leaving, her mother sewed Danticat 10 dresses, most of them too

big, so that she could still dress her daughter after she was gone.

In her uncle and aunt's house, Danticat shared a room with their adopted

daughter, Marie Micheline, who would whisper to Danticat the story of

the butter cookies Mira would buy for his little girl on his way home.

As a toddler, Danticat didn't care for the cookies, but she would hoot

with laughter and feed them to her papa.

" 'He loved you so much,' [Marie Micheline] would say out loud

at the end of the story, 'he left you with us.' " Marcel Proust's

stale old madeleine doesn't have anything on Marie Micheline.

With no phone at home, letters were their primary connection. Every

other month, her father would mail a three-paragraph letter, carefully

avoiding any overly personal topics that might cause his children pain.

Her uncle created a ceremony to honor the importance of those paragraphs.

In college, Danticat writes, she found out her dad's letters were written

in a "diamond sequence, the Aristotelian 'Poetics' of correspondence."

Later, he said to her, "What I wanted to tell you and your brother

was too big for any piece of paper and a small envelope."

Words remained a powerful symbol between Danticat and her father, even

though, she writes, the two always carefully avoided any emotional conversations.

When she and Bob rejoined their parents in New York, her dad gave her

a Smith-Corona Corsair portable typewriter as a welcome-home present.

" 'This will help you measure your words,' he said, tapping the

keys with his fingers for emphasis." Her dad meant it literally

– both Danticat and her dad's cursive had a tendency to run downhill

– but the gift turned out to be a prescient one.

Danticat recalls her uncle with great affection. She writes about small

treats, such as a shopping trip where her uncle bought her a shaved

coconut ice and a secondhand book ("Madeleine"), as well as

the time Joseph risked his life to save Marie Micheline and her baby

from an abusive husband. Her uncle and aunt took a number of children

into their pink house in the Bel Air neighborhood of Port-au-Prince,

as well as running a church and a school.

Despite Mira's urgings to join him in America, Joseph refused to abandon

his church – even when an emergency surgery left him without a

voice with which to preach. Coups and the growing riots in his neighborhood

couldn't shake him. Then gangs burned the church down and began hunting

for Joseph. His escape from Port-au-Prince was worthy of Houdini, but

the miracle was short-lived.

After arriving in Miami and asking for asylum, the octogenarian was

sent to the Krome detention center, where his medication was taken away.

Perhaps to avoid charges of embellishment, or perhaps because it's just

too painful, Danticat keeps adjectives to a minimum and largely lets

the government's own documents tell of her uncle's final days.

Mira ended up outliving his brother long enough to hold Danticat's daughter,

whom she named for him. "I wish I could fully make sense of the

fact that they're now sharing a grave site and a tombstone in Queens,

N. Y., after living apart for more than 30 years," she writes at

the conclusion of her memoir.

"In any case, every now and then I try to imagine them on a walk

through the mountains of Beausèjour.... And in my imagining,

whenever they lose track of one another, one or the other calls out

in a voice that echoes throughout the hill, 'Kote w ye frè m?

Brother, where are you?'

"And the other one quickly answers, 'Nou la. Right here, brother.

I'm right here.' "

• Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.

*********************************************

********

Fall

Preview 2007 - Book

In

Loving Memory

Edwidge

Danticat’s new book relates the lives—and deaths—of

her beloved father and uncle.

by Michael

Miller,

September

12, 2007, Time

Out New York

At a time when most American memoirs

practically groan under the weight of self-importance and bad-memory

baggage (check out Brock Clarke’s rant on page 32), Edwidge Danticat’s

Brother, I’m Dying provides a formidable example of an author

who knows how to write about her family without hogging the stage.

The writer refers to herself, sure,

but never at the expense of her true subjects: her father, Andre, who

emigrated from Haiti to Brooklyn in 1971; her uncle, Joseph, a preacher

who remained in Port-au-Prince; and the ways that their lives radically

differed until they converged in death.

“The idea wasn’t to talk about myself,” says the 38-year-old

author, best known for novels such as Breath, Eyes, Memory. “I

set off trying to write about these two men and the fact that for 30

years, they lived in different countries, had very different lives,

and all of a sudden, they’re both buried in Queens.”

Death hovers over chapter one, set in July 2004, when the author learns

that Andre is suffering from pulmonary fibrosis. From there, Brother

conjures up vibrant episodes in the Danticat family history in a tone

that’s both clear-eyed and mythical. One typical chapter tells

of Joseph’s throat-cancer diagnosis, and his trip to the U.S.

to undergo a laryngectomy. He returns to Haiti voiceless.

“There were many moments when I thought that my father’s

and my uncle’s lives were like folklore,” the author says.

“You know, going to the enchanted land and never coming back,

or coming back without the ability to speak.”

Interspersed with these stories of near wonder are scenes of political

turmoil in Haiti, which push the book toward its haunting moral core.

In October 2004, after gangs threaten to kill Joseph, the preacher flees

to Miami, where he’s detained by immigration officials. After

a series of seizurelike attacks that go untreated, he dies.

Danticat and her ailing father requested a report on what had happened.

“The first bunch of papers we got was 35 pages, with only two

you could read—everything else was blacked out,” she recalls.

“Eventually we got the rest.” With the help of these documents,

Danticat re-creates her uncle’s final hours in masterful detail.

“I wanted to lay out the facts, to tell a story and to let people

come to their own conclusions,” she says. But by the end, it’s

impossible not to feel outrage at the bureaucracies that denied Joseph

his humanity and his life.

Brother, I’m Dying (Knopf, $24) comes out Mon 10.

*********************************************

|

|

Examples

of Neocolonial Journalism on Haiti

|

| **********************************************

“Be true to the highest within your soul and then allow yourself

to be governed by no customs or conventionalities or arbitrary man-made

rules that are not founded on principle.” Ralph

Waldo Trine

***********************************************************

HLLN's

Work

from the HLLN pamplet

"...HLLN dreams of a world based on principles, values, mutual

respect, equal application of laws, equitable

distribution, cooperation instead of competition and on peaceful

co-existence and acts on it. We put forth these ideas, on behalf of

voiceless Haitians, through a unique and unprecedented combination of

art

and activism,

networking, sharing info on radio interviews, our Ezili Danto listserves

and by circulating our original

"Haitian Perspective" writings. We make presentations

at congressional briefings and at international events, such as An

Evening of Solidarity with Bolivarian Venezuela.

With the Ezili

Danto Witness Project, HLLN documents eyewitness testimonies

of the common men and women in Haiti suffering, under this US-installed

regime, the greatest forms of terror and exclusion since the days of

slavery; conducts learning forums on Haiti (The "To-Tell-The-Truth-About-Haiti"

Forums), and , in general, brings the

voices against occupation, endless poverty and exclusion

in Haiti directly to concerned peoples worldwide - people-to-people

and then to governments officials, international policymakers, human

rights organizations, journalists, the corporate and alternative media,

schools and universities, solidarity networks. We are often quoted in

major alternative and even the corporate papers and press influencing

the current thinking of readers today."

HLLN, November 9, 2005.

See, The Nescafé

machine, Common Sense, John Maxwell Sunday, November 06, 2005 , quoting

HLLN's chairperson, Marguerite Laurent, Esq.

*********************************************

Ezili

Dantò's Note: Bwa Kayiman 2007 and the case of Lovinsky Pierre

Antoine Pierre

|